ce qu'on a oublié de vous dire sur Tienanmen

Il fallait bien cacher la vérité au monde et ne surtout pas dire que les manifestations pour la liberté de 1989 ont débuté par des protestations et émeutes raciales à la suite de rumeurs de viols de chinoises par des étudiants africains et d'incidents (i.e. rapprochements sexuels) impliquant des noirs et des chinoises.

extrait du livre “La face cachée de la Chine” de Jean-Marc et Yidir Plantade sur ilikeyourstyle.net :

http://ilikeyourstyle.net/index.php/2006/10/05/la-verite-sur-tienan-men/

Combien, parmi le grand public, savent que les évènements de la place Tianan men de 1989 ont eu comme prélude des émeutes anti-étrangers? En effet, depuis les années soixante, la Chine, au nom de la solidarité prolétarienne et tiers-mondiste, accueille un grand nombre d’étudiants africains, à qui elle propose des bourses supérieures à celles qu’elle octroie aux étudiants chinois. Cette situation « privilégiée » des Africains à l’université, ainsi que des préjugés tenaces à l’égard des Noirs, provocait régulièrement des coups de colère de la part de certains étudiants chinois. L’hostilité à l’égard des subsahariens se faisait particulièrement sentir lorsque des contacts publics avaient lieu entre des garçons africains et des jeunes filles chinoises. Le premier incident anti-africain répertorié date de 1979, à Shanghai, lorsque des étudiants africains sont attaqués alors qu’ils jouent de la musique à fort volume sonore en compagnie de jeunes Chinoises. Ce type de fait divers devient de plus en plus courant durant les années quatre-vingt et culmine le 24 décembre 1988. Ce jour-là, deux étudiants africains cherchent à entrer avec deux jeunes chinoises sur le campus de l’université Hehai, a Nankin, pour participer à un réveillon de Noël. Devant la demande du gardien de vérifier les papiers d’identité des jeunes femmes, une querelle éclate et dégénère en une bagarre générale entre étudiants africains et chinois, qui dure jusqu’au petit matin. Treize personnes sont blessées au cours de la nuit. Dans la journée du lendemain, une rumeur court disant que les Africains ont tué un Chinois pendant la nuit. Trois cents étudiants chinois se réunissent alors et défoncent le portail de la résidence des étudiants étrangers, détruisant les dortoirs et hurlant « Sha hai hei gui ! » (« Tuons les démons noirs » ! ). Les étudiants africains, ainsi que les autres étrangers, 140 personnes au total, tentent de fuir vers la gare, où la police leur refuse le droit d’embarquer. Le 26 décembre, une manifestation de 3000 étudiants se dirige vers la gare et demande pour la première fois, outre l’expulsion des étrangers, le respect des droits de l’homme et des réformes politiques. Ces manifestations durent plusieurs jours et sont réprimées par la police antiémeute. Ces manifestations anti-étrangers (particulièrement anti-Africains) se propagent à Shanghai et à Pékin, où elles sont considérées comme un des éléments déclencheurs du Printemps de Pékin, qui a lieu quatre mois plus tard, à l’occasion des funérailles de Hu Yaobang (ex-secrétaire général du parti, considéré comme un réformateur).

en anglais:

auteur: Erin Chung. Écrit pour The Institute for Diasporic Studies chez la Northwestern University. On peut voir la page originale ici sur archive.org:

http://diaspora.northwestern.edu/cgi-bin/WebObjects/DiasporaX.woa/wa/displayArticle?atomid=711

Beijing students protest an alleged rape by one of the foreign students. Time Magazine, Jan 16, 1989

Nanjing Anti-African Protests of 1988-89

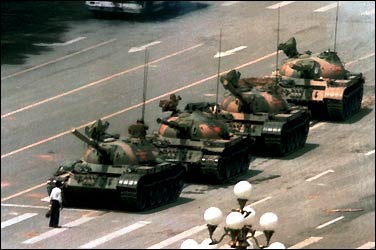

From December 1988 to January 1989, students in Nanjing, China waged violent protests against visiting African students. These protests became the precursor to the nationwide pro-democracy movement in the spring of 1989, which resulted in the massacre of Chinese students by armed troops in Tiananmen Square. Displaying an uneven combination of racial tension, nationalism, and reformism, the Nanjing protests fused mass hostility toward visiting African students with official nationalist discourse to create the momentum for a popular movement for political change. At the same time, they marked the denouement of China's proclaimed leadership of the "Third World" with long-term consequences for Sino-African relations. Yet, these protests were neither isolated events, as the Chinese government claimed, nor simply outbreaks of general xenophobia directed at all foreigners. Frank Dik�tter has traced various discourses of race in China from the late nineteenth century based on myths of origins, ideologies of blood, and narratives of biological descent that have been central to the cultural construction of Chinese identity. Barry Sautman attributes the rise of anti-Africanism among the Chinese intelligentsia in the reform era (1978-present) to the return of racial stereotyping and elitist values dating back to Imperial China that link and denigrate those who are dark and those who are poor.

(...)

The Nanjing protests in December 1988 were triggered by a series of confrontations between African and Chinese students at Hehai University. The conflict intensified on December 24 when two African male students who were escorting two Chinese women to a Christmas Eve party on campus were stopped at the front gate and ordered to register their guests. A new university regulation that restricted registration procedures for guests visiting foreign students had been implemented in October of that year to stop African male students from consorting with Chinese women in their dormitories. A quarrel between one of the African students and the Chinese security guard escalated into a brawl between African and Chinese students that lasted until the next morning and resulted in the injury of eleven Chinese and two Africans. On the next day, 300 Chinese students, angered by a rumor that a Chinese man had been killed by an African student the previous evening, stormed the African students' dormitory chanting, "Kill the Black Devils!" The police arrived to restore order two hours later. Fearing for their safety, over 60 African students left for the railway station to reach their embassies in Beijing. Local authorities prevented them from boarding the trains in order to retain those involved in the Christmas Eve brawl. In response, about 140 foreign students, including other African students in Nanjing and a dozen non-African foreign students, sat-in at the train station to demand that they be allowed to board a train for Beijing.

Meanwhile, Chinese students at Hehai University mobilized students from other universities in Nanjing to protest what was perceived as special treatment for foreigners and to demand justice for the alleged murder of a Chinese man the night before. Approximately 3,000 students marched in the streets, singing the national anthem and chanting, "Down with Black Devils!" On December 26, the student demonstrators from Hehai University marched to the provincial government office to demand that the African students be held responsible for their crimes according to the full force of Chinese law. Holding a banner that read, "Protect Human Rights," the demonstrators demanded the reform of a corrupt legal system that privileged foreigners at the expense of ordinary Chinese. That evening, a group of more than 3,000 Chinese students marched to the railway station with banners calling for the protection of human rights, political reform, and justice. The African students were immediately sequestered by the police to a military guest house in Yizheng, 60 kilometers northeast of Nanjing. The police declared the student demonstrations illegal and, with the help of riot police from neighboring provinces, quelled the demonstrations in the next few days. By early January 1989, the authorities arrested and deported three African students from Hehai University who were suspected of instigating the Christmas Eve brawl and sent the remaining students back to Nanjing. The African students were instructed to report to their school authorities before leaving their campuses and to not go out at night. Furthermore, the Hehai University president, Liang Ruiji, announced that African students were required to continue registering their guests at the front gate and were restricted to no more than one Chinese girlfriend whose visits would be limited to the lounge area.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home